How Spain built Manila

Museo San Agustin opens Spanish engineering exhibit

TO recognize the work of individuals who designed infrastructure as far back as the 16th century, Museo San Agustin and the Embassy of Spain recently opened the exhibit “Four Centuries of Spanish Engineering Overseas.”

Within the church museum’s old stone walls in Intramuros lie illustrations, blueprints, and reports of projects by engineers of the Spanish Crown. These items constitute a great technological heritage in the history of humanity, according to Maria Antonia Colomar, one of the exhibit’s curators.

“When the Spaniards arrived, cities and towns were formed, becoming the nerve center of a new system of organizing the territories and their landscape,” she said in Spanish at the exhibit’s opening on March 14.

Ms. Colomar added that this homage to the work of overseas military engineers was first exhibited at the General Archives of the Indies in Seville in 2018. Its current adaptation in the Philippines is enriched with pieces related to the archipelago, displayed for the first time in different parts of the exhibit.

It also divides the enormous body of work into various branches: urban planning and territorial organization, hydraulic works, communications, mining, industry, ports and fortification, and naval engineering.

“This is a very ambitious exhibition because it covers four centuries, from the 16th to the 19th century, in both American territories and the Philippines,” said co-curator Ignacio Sanchez de Mora in his opening speech.

The exhibit shows how the “building of the territory” took place by merging European-style infrastructures with pre-Hispanic precursors.

“We’d like to attract the youth to study engineering, enhance their understanding of its concepts, and inspire researchers who have yet to discover the importance of this specific field,” said Mr. Sanchez de Mora.

SAN AGUSTIN CHURCH

Rev. Fr. Ricky B. Villar, director of Museo San Agustin, added that the year 2024 is a significant milestone for the San Agustin Church in particular. Completed in 1604, it now celebrates 420 years of existence.

“How this building lasted for four centuries in spite of different manmade and natural calamities and unfortunate events is a testament of both the structure’s strong foundation and the enduring legacy of the friars,” he said.

The church was declared a world heritage site in 1993. Its core structure remained miraculously intact even after the intense bombing during World War II which leveled Intramuros. It still survives thanks to conservation efforts.

Not all marvels of Spanish engineering are as lucky, however.

For Ms. Colomar, one of the things that excited her about bringing the exhibit to the Philippines was seeing in person the areas where structures that she had been studying were, such as the “Puente Grande” over Pasig River.

“I was excited to actually see the first bridge to ever cross the river, built by Augustinian friar Antonio Herrera in 1630 to connect Intramuros and Binondo. I didn’t realize it had been damaged by an earthquake in 1863 and later destroyed by flood in 1914,” Ms. Colomar said in Spanish.

She added that its fate, along with that of much of the infrastructure from the colonial period, goes to show how different the terrain and weather is in the Philippines. The bridge that stands in Puente Grande’s place today is Jones Bridge.

MAPS

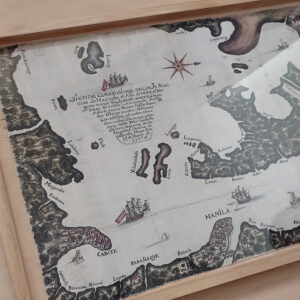

Among the 80 exhibition items that may fascinate Filipino visitors are a 1663 plan for improving the defenses of the square of Cavite; a 1715 map depicting Subic as a timber-producing shipyard; an 1814 sketch of Manila and the port at the mouth of Pasig River; and a railway plan for Luzon drafted in 1876, seen today in the Philippine National Railway.

A notable donated item is a copy of the Murillo-Velarde map from 1734, used as proof that Scarborough Shoal and the Spratly Islands are part of the Philippines. In the map they are labeled as Panacot shoal and Los Bajos de Paragua, respectively.

Items pertaining to the Philippines, interspersed among others showing infrastructure built in Mexico, Peru, Argentina, Chile, and other Hispanic territories in South America, highlights the amount of work engineers had put in across decades and even centuries.

“While most original copies of plans are in Madrid, the Philippines most likely has copies as well in its national archives since maps and sketches often have various ‘originals’ made,” Ms. Colomar said.

She emphasized the enormity of the contributions made by colonial engineers in developing cities and societies, a part of history that Filipinos can study and draw inspiration from moving forward.

The exhibit runs until Dec. 14 at the Museo San Agustin, General Luna St., Intramuros, Manila. The museum has an entrance fee of P200 for adults and P160 for students, PWDs, and senior citizens. — Brontë H. Lacsamana