Malnutrition and the Agency Problem

In business education, there is a subject called “The Agency Problem.”

Modern corporations are owned by numerous stockholders who have neither the time nor the talent nor the inclination to manage the corporation. The solution is to hire professionals called management who will manage the corporation in the best interest of the stockholders. The problem is that the management (the Agent) may not act in the best interest of the stockholders (the Principal), hence “The Agency Problem.” For clearly the interests of the agent do not always align with the interests of the principal. Thus, in matters of executive compensation the interest of the principal is to frugally pay the agent based on the performance of the company while the interest of the agent is to be lavishly paid no matter how well or badly the company performs.

As with the private sector, so too with the public sector, with greater complexity. We the citizens (the Principal) elect politicians (the Agent) who are expected to act in our best interest. Due to the complexity of modern governments, the politicians will in turn appoint unelected officials called bureaucrats (the Agent’s Agent) who will administer the government machinery on their behalf. The Agency Problem arises when our interests (the Principal) conflict with the diverse interests of the politicians (the Agent) and the bureaucrats (the Agent’s Agent).

Contrary to popular belief, politicians, not bureaucrats, are more likely to act in the best interests of citizens as they must be elected while career bureaucrats have security of tenure. Thus, in the case of our traffic problem, we can rely more on our political leaders rather than our transportation bureaucrats who seem to define their interest as stifling the private sector initiatives such as Grab and Angkas to solve our traffic problem. (By the way, they cannot even deliver our car plates on time)

As with our traffic problem, so too with our malnutrition problem.

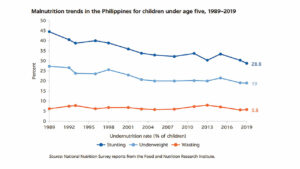

The World Bank report on patterns of nutrition in the Philippines noted that for nearly 30 years, rates of both wasting and stunting have been nearly flat. Figure 2.1 shows under-nutrition trends in the Philippines for children under age five. Wasting indicates that a child has low weight for his or her age and is a sign of acute, short-term malnutrition. The prevalence of wasting in 2019 (5.8%) was similar to what it was 20 years previously. Stunting, meanwhile, indicates that a child is, loosely speaking, short for his or her age. The rate of stunting fell through the early 2000s but has remained almost flat since then. The rate of stunting recorded for 2019 (28.8%) was only slightly lower than the 2008 level.

The Agent’s Agent designated to deal with our malnutrition problem is the National Nutrition Council chaired by the Secretary of Health. The primary function of the council is to prepare the Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition (PPAN 2023-2028).

To implement this plan requires a chain of agents who must follow the plan. Any break in the chain will mean that the plan will fail. Most often failure occurs at the last link, in this particular case the barangay, which is either unable or unwilling to provide the necessary healthcare for the person in most need of it, the poor or near-poor mothers.

Several NGOs, particularly the Zuellig Family Foundation chaired by Ernesto Garilao, have sought to forge this final chain by programs aimed at developing and institutionalizing the nutritional activities of the lowest Local Government Units, the Barangays.

But another approach is the Indian approach.

In its May 21, 2022 cover story on India, The Economist noted that the Indian government used a direct, real-time, digital welfare system to pay $200 billion over three years to about 950 million people. How did this come about?

In January 2013, the government of India introduced the Direct Benefit Transfer or DBT scheme to streamline the transfer of government-provided subsidies from various Indian welfare schemes directly into the beneficiaries’ bank accounts. This has been one of the most ambitious financial inclusion initiatives ever seen anywhere in the world, bringing over 330 million people into the formal financial sector.

By 2020, 318 subsidy schemes from 53 ministries have been directly transferred to the farmer beneficiaries. And the program is so successful that India is now a wheat and rice exporter.

Using the Indian approach which relies on harnessing the technology of direct access to intended beneficiaries, we could bypass this chain of agents and give aid directly to the poor or near-poor mothers through food stamps, PhilHealth vouchers, or even cash vouchers.

Moreover, we already have the existing framework for successfully bypassing the non-performing agents.

As reported by the World Bank, the conditional cash transfer (CCT) program locally known as Pantawid Pamilya Pilipino Program, or 4Ps, is a government program that provides conditional cash grants to the poorest of the poor in the Philippines. The program aims to break the cycle of poverty by keeping children aged 0-18 healthy and in school, so they can have a better future. The program is implemented by the Department of Social Welfare and Development, with the Departments of Health and Education and the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) as partners.

Households receive cash grants if children stay in school and get regular health check-ups, have their growth monitored, and receive vaccines. Pregnant women must get pre-natal care, with their births attended to by professional health workers. Parents or guardians are required to participate in monthly community-based Family Development Sessions to learn about positive child discipline, disaster preparedness, and women’s rights. Beneficiaries are objectively selected through the National Household Targeting System, also known as Listahanan, which is based on a survey of the physical structure of their houses, the number of rooms and occupants, their access to running water, and other factors affecting their living conditions.

The program has one of the most comprehensive poverty targeting databases in the world today, covering 75% of the country’s population. It has been used extensively to identify poor and near-poor beneficiaries for national and local government programs.

Started in 2007 by then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo at the advice of then NEDA Director General Romulo L. Neri, the government expanded the program in December 2016 to reach a total of 20 million Filipinos belonging to 4.4 million households. The program benefits about 20% of the population. The majority of the nation’s 9 million poor children are currently benefiting from the program, 1.9 million of whom are in high school. The program has also achieved almost universal enrollment for elementary age children of 4Ps households.

Social protection programs, Pantawid included, have cushioned the poor from the adverse impacts of various shocks the country experienced over the past six years. A study estimates that the program has led to a poverty reduction of 1.4 percentage points per year or 1.5 million less poor Filipinos. The 4Ps is currently the world’s fourth-largest CCT program based on population coverage. It complements the government’s other development priorities such as generating jobs and creating livelihood opportunities for the poor.

All that is needed is to attach to the 4Ps program, which already has access to the poor and near-poor mothers, the programs that are not presently being delivered by the Barangay Nutrition Action Team.

Dr. Victor S. Limlingan is a retired professor of the AIM and a fellow of the Foundation for Economic Freedom. He is presently chairman of the Cristina Research Foundation, a public policy adviser of Regina Capital Development Corp., and a member of the Philippine Stock Exchange.