The Philippines is battling a resurgent Islamic State threat

WHEN THE BLAST ripped through the gymnasium of the Mindanao State University in Marawi, it was packed with worshippers, many of them students deep in prayer during Sunday Mass. The timing of the attack was significant — around 7 a.m. on the First Sunday of Advent, the start of the traditional four-week preparation for Christmas which holds special meaning for the majority-Roman Catholic nation.

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. swiftly condemned the assault as “heinous acts perpetrated by foreign terrorists.” Islamic State has since claimed responsibility on its Telegram channel, and while authorities say they’re still investigating, they have launched a “massive manhunt” to find the suspects. The bombing killed four people, and at least 50 were injured, according to the Philippine military.

The southern part of the archipelago is no stranger to this kind of violence, but over the last few years there had been relative calm in an area that was once a stronghold of Islamic State-led terrorists. Now, there are concerns that the group is gaining new momentum. The Philippines must crack down on any nascent threats, while simultaneously working on understanding and addressing long-standing resentments among Muslims in Mindanao.

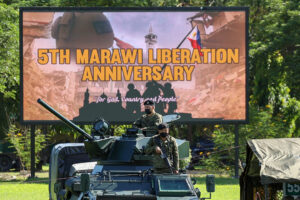

The alternative would be a return to the brutality of the past. In 2017, Marawi was the scene of a five-month battle between the Philippines military and Islamic State-led fighters. It was a grueling urban conflict, with militants aiming to turn Marawi into the capital of a Southeast Asian province of their Muslim caliphate. After months of fighting, the Philippines regained control of the city, backed by American and Australian airstrikes and surveillance. Two senior IS leaders were also killed. By some estimates, 400,000 people were displaced, and since then, Marawi has been in the slow process of restoration and recovery. The central government has reached peace accommodations with different, more mainstream separatist and sectarian groups that include elections, but the most extreme elements surface periodically. It’s too early to say how much traction they’ll gain this time.

“The blast in Mindanao State University is part of the ISIS followers attempt to recapture Marawi,” Rommel Banlaoi, chairman of the Manila-based Philippine Institute for Peace, Violence and Terrorism Research told me. “The aim is to start up a new round of violence to establish the Islamic State in the Philippines.”

This is not a new goal. Islamic State has always capitalized on the long history of armed struggle in the predominantly Muslim region to achieve autonomy or more from the Catholic majority Philippines. But the Hamas attack on Oct. 7 that killed 1,200 Israelis and foreign nationals and took as many as 240 hostage, may be driving a new security threat. As Israel’s military response pushed the claimed civilian death toll in Gaza above 15,900, and with images of dead and injured children flooding their timelines, Muslims across Asia have attended rallies and sermons in support of Palestinians. While there has been no direct link announced between the violence in Gaza and the Marawi bombing, the situation is one that IS militants have been able to exploit in their attempts to find new recruits.

There’s also the added element of internal rivalry between terror groups, as they advance longer-range agendas, Greg Barton, chair in Global Islamic Politics at the Melbourne-based Deakin University told me. “The Islamic State, which has historically criticized Hamas for not being hardline enough, may feel under pressure to put itself back in the spotlight.”

Heavily damaged in the five months of fighting and occupation six years ago, Marawi is now slowly being rebuilt, but thousands of people have yet to return to their homes or their old lives. The glacial pace at which the reconstruction of the city has been moving has only added to decades of failure to make good on promises to improve the chronically poor region. Separatism was nothing new, but by 2017, the Philippines was seen as a prime target for Islamic extremism helped by the presence of already active Islamist militant groups. Understanding and addressing the inherent resentment among this community is key to fixing long-standing grouses that could erupt into fresh tensions.

Sidney Jones, director of the Jakarta-based Institute for Policy Analysis Conflict, predicted the lasting appeal of ISIS in the Philippines in 2019, urging the nation to move beyond military operations aimed at killing known extremist leaders, which only produces a new generation bent on vengeance.

The administration, then led by the hard-nosed Rodrigo Duterte, may have changed, but the problems for Marcos Jr. remain the same. One solution would involve reintegrating American assistance into fighting terror networks, a practice that existed for several years after 9/11, with US special forces supporting counterterrorism units in the Philippines. The US is estimated to have spent some $3.9 billion to try to eliminate the terror threat on the archipelago. It then began winding down its operations in 2015, although the Americans have come back to help periodically over the years. Given the current situation in Gaza and Ukraine, and potentially Taiwan, it is unlikely Washington has the capacity to meaningfully help Manila to ward off future militant threats.

The Philippines could learn from Indonesia’s success in fighting terror by separating the military from counterterrorism activities. A number of ambitious plots were thwarted by the country’s special police unit Densus 88 (Special Detachment 88), as this report notes,* including an attempted attack on the tourist island of Bali and a plot to bomb the presidential palace.

Another solution that has been floated is implementing the controversial 2020 Anti-Terrorism Law more effectively. Passed under Duterte’s administration, the law allows warrantless detention and wiretapping of suspected terrorists, which was criticized at the time by the country’s human rights commission. Better still, as Jones points out in her report, would be “finding a non-military strategy aimed at addressing the causes of radicalization and preventing the regeneration of militant groups.”

None of this is easy, but it is all the more urgent in the face of rising resentment over the continued suffering in Gaza. It is an explosive issue and one that is ripe for exploitation by terror networks looking to find fresh recruits. Manila must be on guard.

BLOOMBERG OPINION